The Unseen Work of a Cloud Architect: A Story About Building Azure the Hard (and Right) Way

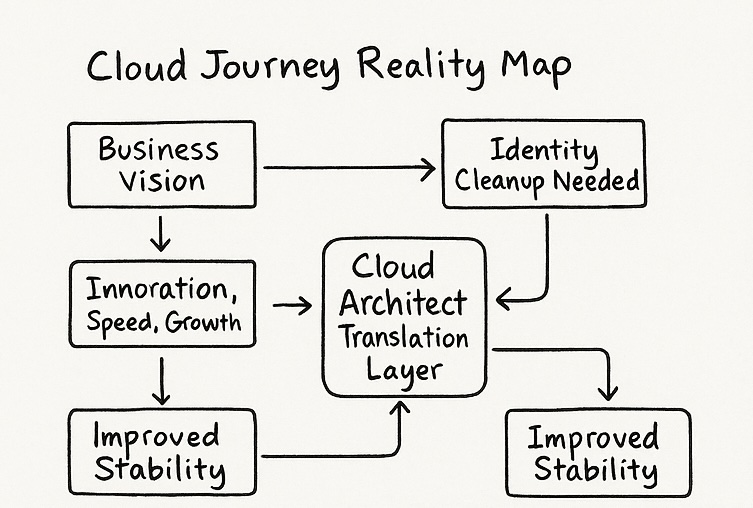

The story of implementing an Azure cloud environment rarely starts with technology. It begins with a seemingly simple conversation: someone in the business has a goal, a team has a new initiative, or an executive has read an article promising faster innovation, better resilience, or lower operational costs. The request sounds straightforward: “We want to move to Azure.” But it’s never that simple. Not because Azure is inherently complex, though it can be, but because cloud architecture is more about managing people, expectations, culture, pressure, and an ever-changing regulatory landscape.

I’ve learned that every Azure journey starts with a promise of possibility. But possibility quickly clashes with reality, turning the cloud architect into a translator, negotiator, strategist, firefighter, therapist, and sometimes the villain who says “No, we can’t do that… yet.”

This story reveals what it genuinely means to implement an Azure cloud environment, not from polished diagrams or landing zone blueprints, but from the trenches where decisions matter, missteps have impacts, and architecture involves negotiation rather than simple design.

The First Meeting: Hope, Pressure, and the Myth of “Just Azure”

It often begins with a room full of people nodding eagerly. Azure is seen as the future, strategic, and aligned with what competitors are adopting. There is a unanimous consensus that the cloud will deliver faster speeds and greater agility, two terms frequently mentioned together in meetings, often alongside a third: innovation.

But underneath the enthusiasm sits a quiet expectation: the architect will take this energy and turn it into something real. Something reliable. Something secure. Something compliant. Something scalable. And something that works on day one.

What many overlook is that even the initial step of defining what “move to Azure” entails unlocks a multitude of decisions. Is it a migration, modernization, or starting fresh with a new platform? What regulations must be considered? How mature is the organization? What is the current security stance? How should landing zone governance integrate with existing processes? And perhaps most critically: what are the real objectives of the business beyond the marketing slogans?

I’ve often observed that the most challenging aspect of cloud adoption is the translation layer. Business units focus on outcomes, finance on budgets, cybersecurity on risks, DevOps on pipelines, engineers on YAML, and leadership on the idea that “the cloud should be cheaper.” This last belief particularly haunts cloud architects more than they typically admit.

Everyone agrees on migrating to Azure, but there is no consensus on what Azure precisely entails.

The Blueprint Nobody Sees

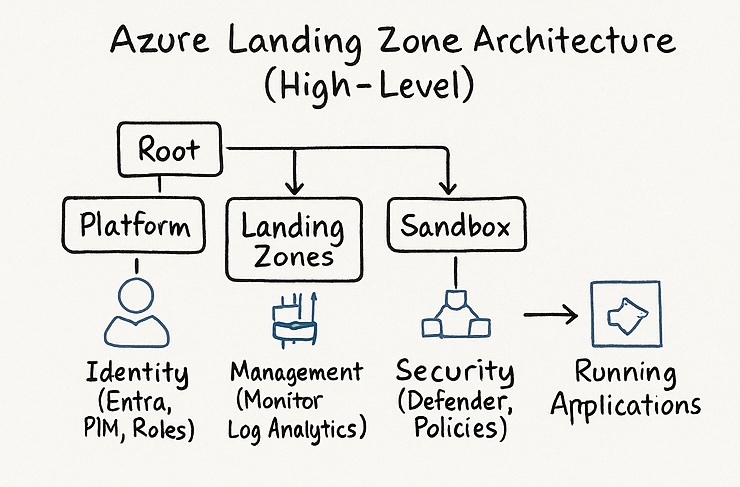

One of the things that still surprises people is how much architecture is invisible. For every visible deployment of an AKS cluster, a virtual network, and a storage account, there are dozens of invisible decisions shaping it. Naming standards, tagging models, identity governance, enterprise app registrations, conditional access policies, region selection strategies, service principal lifecycle, cost ownership, FinOps guardrails, and compliance controls that exist precisely so nobody notices when they work.

A cloud architect typically focuses on these key areas, but many people assume Azure automatically handles them. People are often surprised to learn that Azure doesn’t enforce naming conventions, establish network baselines, segment privileged access, or prevent developers from accidentally deploying a public IP from their laptops.

Azure gives you the tools. The architect builds the system around them.

Designing such a system becomes more complex because architecture does not develop in isolation. Instead, it operates within an ecosystem of legacy systems, existing governance, entrenched processes, siloed teams, cautious security departments, underfunded operations, and developers who usually want the cloud but resist the guardrails.

The irony is that the most well-designed cloud environments seem simple and effortless. However, this simplicity results from making countless difficult decisions, most of which are settled long before the first workload is deployed in Azure.

Identity: The First Real Battle

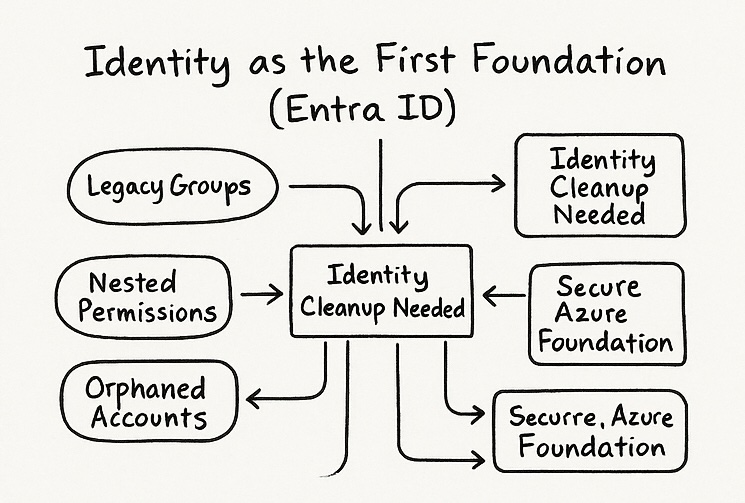

If you ever want to test a cloud architect’s patience, ask them about identity. Every cloud journey inevitably hits the wall called Entra ID, and the crash is rarely graceful.

Identity bridges the gap between abstract cloud goals and real business needs. It’s no longer just about elegant architecture; it’s about controlling who can do what, why, and whether the organization truly manages its directory to handle enterprise apps, privileged roles, or guest accounts. You encounter deeply nested groups, forgotten service principals with full permissions, orphaned accounts of former employees, and admins clinging to global admin rights “just in case.”

The conversation shifts from architecture to sociology. Identity reflects an organization’s history more than its engineering principles. Cleaning it up feels like excavating a digital archaeological site.

However, this is also the point where the cloud architect must begin to establish a structured framework. This includes defining Administrative Units, implementing privileged access workflows, creating custom roles, enforcing separation of duties, conducting access reviews, and developing a governance model that prioritizes identity as the primary security boundary instead of an afterthought.

Every Azure environment must start with identity, as everything else relies on it. Despite its importance, identity is often underestimated, making it the initial challenge and a frequent point of political contention.

Networking: Where Every Decision is Permanent

You can update policies, reassign roles, or restructure resource hierarchies. However, networks are fixed once established. Selecting address spaces, region topology, and isolation boundaries ties your organization to long-term architectural choices that are difficult and costly to change later.

The cloud architect knows this. Leadership often doesn’t.

Networking often involves balancing future flexibility with current limitations. You might advocate for a hub-and-spoke or virtual WAN setup. Someone may suggest, “Just do peering for now,” and you’ll need to explain what that entails. They’ll argue it’s only temporary. A year later, what was supposed to be temporary becomes permanent, and the architecture turns into a negotiation with the ghosts of past choices.

Hybrid connectivity serves as the great equalizer of ambition. It includes ExpressRoute, VPNs, firewalls, BGP, overlapping IP ranges, legacy environments with undocumented address spaces, and the persistent belief that connecting the cloud to on-premises systems simply requires purchasing the right SKU.

Azure networking is powerful, flexible, and comprehensive. However, implementing it demands a persistent focus on long-term maintainability. Every shortcut becomes a cost that the cloud architect must pay later.

Security: The Part Everyone Wants Until It Slows Them Down

Cloud security is a topic everyone agrees is important until it slows things down. The struggle between innovation and safety drives cloud architecture, and that’s most evident in security design.

You propose Zero Trust. People agree. You suggest segmenting workloads. They agree. You recommend managed identities, proper certification rotation, and service principals with minimal privileges. They agree again. Then a developer requests Owner permissions on the subscription “just for a few days,” and suddenly the agreement ceases.

Security involves balancing boundaries. If it’s too lenient, you’re setting up for future incidents. If it’s too strict, you become a bottleneck that everyone criticizes.

Threat modeling, least privilege, securing service boundaries, policies, conditional access, Privileged Identity Management, Defender for Cloud, network controls, and key vault governance are not visible in the final application diagram. However, all of these elements influence the environment’s security.

The cloud architect is responsible for saying “no,” even if it’s unpopular. They need to remind teams that control isn’t the enemy of innovation, chaos is. However, that message often doesn’t resonate on the first try.

Compliance: The Invisible Hand of European Cloud Architecture

Being a cloud architect in Europe involves more than just designing systems; it requires navigating regulations such as GDPR, DORA, NIS2, and sector-specific rules that shape the environment before deploying an Azure resource. You must consider data sovereignty, residency, legal liabilities, audit trails, and ensure every service complies with increasingly strict standards.

It encourages a new perspective on boundaries. Regions now matter beyond just latency, affecting sovereignty controls, encryption models, and service classifications that shape your landing zone. Operational processes now become integral to architecture.

Azure offers sovereign controls, customer-managed keys, regional restrictions, private endpoints, and policy-driven governance, but using these features effectively requires discipline. Explaining them to non-technical stakeholders can also be a challenging art.

Compliance is rarely the hero of the story, but it quietly shapes every chapter.

FinOps: Where Architecture Meets Reality

Someone always inquires about the cost. Sometimes it’s too early, but mostly it’s late, often right after the first bill arrives.

FinOps presents a distinct challenge for cloud architects because cloud economics differ significantly from traditional IT budgeting. While the cloud offers elasticity, this flexibility needs proper governance. Without governance, Azure risks turning into a space filled with abandoned POCs, neglected managed disks, oversized databases, and environments lacking ownership.

You can design an ideal architecture, but without accountability for spending, it becomes unsustainable. Thus, the architect’s role shifts to that of an educator, guiding product owners to see cost as a feature rather than an afterthought. They introduce tagging, enforce budgets, set up alerts, define ownership, and incorporate cost insights into operational workflows. They also advocate for automation to eliminate unused resources.

FinOps is not a discipline that creates barriers. Instead, it helps prevent cloud adoption from failing due to its complexity. As with security, its benefits are usually acknowledged only after it prevents the organization from making potential errors.

Landing Zones: The Promise and the Pain

Landing zones are frequently viewed as the ultimate solution. They address governance, security, consistency, compliance, and operational readiness.

But they don’t solve the most challenging part: getting consensus.

A landing zone isn’t just a template; it’s a binding agreement among teams. It specifies ownership, workload behaviors, and environment interactions. It formalizes decisions that many teams might prefer to keep ambiguous. Because it brings clarity, it often faces resistance.

Choosing management groups becomes a debate over organizational responsibility. Policies are scrutinized in debates over autonomy. Network architecture shifts into a proxy battle between teams advocating for centralization and those seeking independence. Identity governance reveals hidden legacy structures that people hadn’t noticed before. As a result, the architect’s role shifts from designing infrastructure to enabling change.

Implementing a landing zone is fulfilling not because of the technology itself, but because it creates coherence within an organization that has outgrown its previous methods.

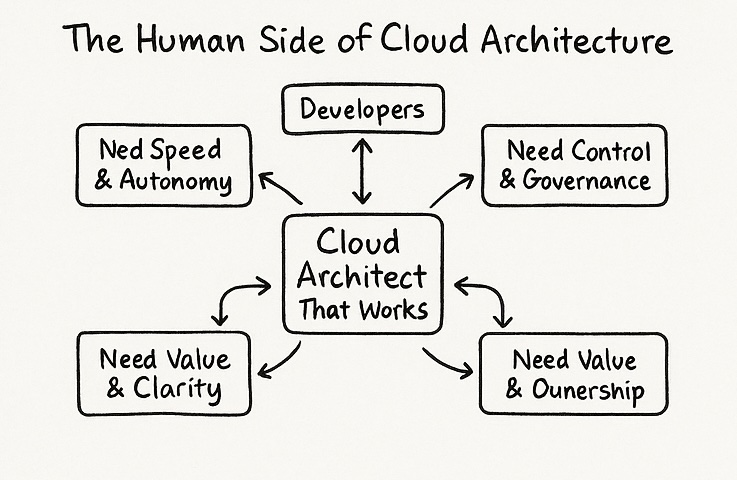

Developers: The Unofficial Customers of the Cloud

No matter what leadership believes, developers are the primary users of the cloud. If the platform doesn’t support them, if pipelines are sluggish, permissions are confusing, environments vary, or guardrails are overly strict, they’ll find ways to bypass it. Developers don’t do this out of malice; they do it out of necessity. Their main goal is to deliver value.

The cloud architect’s responsibility is to create a platform that allows developers to move quickly without causing issues. This involves well-crafted pipelines, self-service deployment options, clear boundaries, predictable governance, and an experience that feels supportive rather than restrictive.

The most effective Azure environments are guided by something many organizations initially overlook: empathy for developers, who use the platform daily. If they don’t enjoy it, no one will.

Operations: The Forgotten Pillar of Cloud Adoption

Eventually, every cloud environment faces real-world operations, including monitoring, logging, alerts, incident response, disaster recovery, backup strategies, automation, and documentation. These factors decide whether the environment endures long enough to generate value.

Operational maturity may not be glamorous; nobody cheers for the alert systems that avert outages or the runbooks used for midnight recoveries. However, these are the foundational elements of cloud reliability.

Azure offers excellent tools such as Monitor, Log Analytics, Managed Prometheus, Automation, Backup, and Site Recovery. However, tools alone are not sufficient. You also need clear processes, ownership, and transparency. Without these, the cloud risks becoming a showcase of great architectural ideas that fail in everyday practice.

People, Culture, and the True Challenge Most Architects Never Mention

Among all the technical challenges, the most difficult part of implementing Azure is the people.

Different teams have varying concerns: some fear losing control, others worry about increased accountability. Some desire total freedom, while others prefer strict governance. Some teams don’t fully grasp the cloud, others misunderstand it, and many resist change.

The cloud architect acts as a link between traditional practices and innovative opportunities. They need to champion guiding principles that may not yield immediate benefits. Their role involves persuading others smoothly, without pressure, while safeguarding the environment from shortcuts, all the while supporting business progress.

This is the emotional labor of cloud architecture, the aspect that rarely appears in reference architectures or diagrams. It demands patience, resilience, and the ability to remain calm amidst conflicting demands. This is what elevates architecture to a form of leadership.

The Moment Everything Finally Works

Every cloud journey has a moment when everything comes together. FinOps dashboards provide clear cost insights. Developers deploy confidently via pipelines. Security teams trust the guardrails. Operations run smoothly without needing constant escalation. Landing zones stop deteriorating into chaos and begin maturing into stability. The business perceives value, not complexity.

This moment often happens quietly without celebration. A team deploys a new service in Azure smoothly, with no issues. It deploys seamlessly, adheres to governance, logs are sent to the proper workspace, costs are stable, permissions are accurate, and there’s no need for emergency access.

This absence of drama signifies architectural success. The cloud appears ordinary, predictable, and dull.

And that’s the goal!

Reflections From the Architect’s Chair

Reflecting on this, the most common misconception about cloud implementation is that it’s mainly a technical task. In reality, while the technical aspects are complex, they are generally predictable. Azure offers established patterns, best practices, landing zone frameworks, and extensive community knowledge. The true challenge of cloud architecture lies in everything surrounding the technology itself.

The issues stem from team misalignment, unclear goals, organizational inertia, conflicting priorities, and governance gaps that existed long before Azure was introduced. Additionally, political resistance to change and human fears of losing control or being exposed contribute to the problem.

Implementing Azure isn’t just about provisioning resources; it involves creating a technical, cultural, and organizational system that can evolve more rapidly than its surrounding environment.

A good architect understands Azure.

A great architect knows how to lead people through change.

An exceptional architect creates a platform so seamless that the organization doesn’t notice the complexity because everything functions effortlessly.

The Ending That Isn’t an Ending

What makes cloud architecture fascinating is that it never really ends. The platform evolves, services change. Regulations shift. New features introduce new possibilities. Workloads move. Teams grow. The architectural story is always in motion.

The role of the cloud architect consistently involves clarifying complexity, guiding chaos, and establishing structure for ambitions. They convert business requirements into technical solutions, safeguard the organization from external threats and internal shortcuts, and create enduring systems that outlast projects, roadmaps, and even the architects themselves.

Azure is a powerful platform. However, the process of implementing it uncovers much more about the organization than about the technology itself. It is in this journey, often messy, political, challenging, and deeply human, that the true art of cloud architecture is discovered.

Want to know more about what we do?

We are your dedicated partner. Reach out to us.